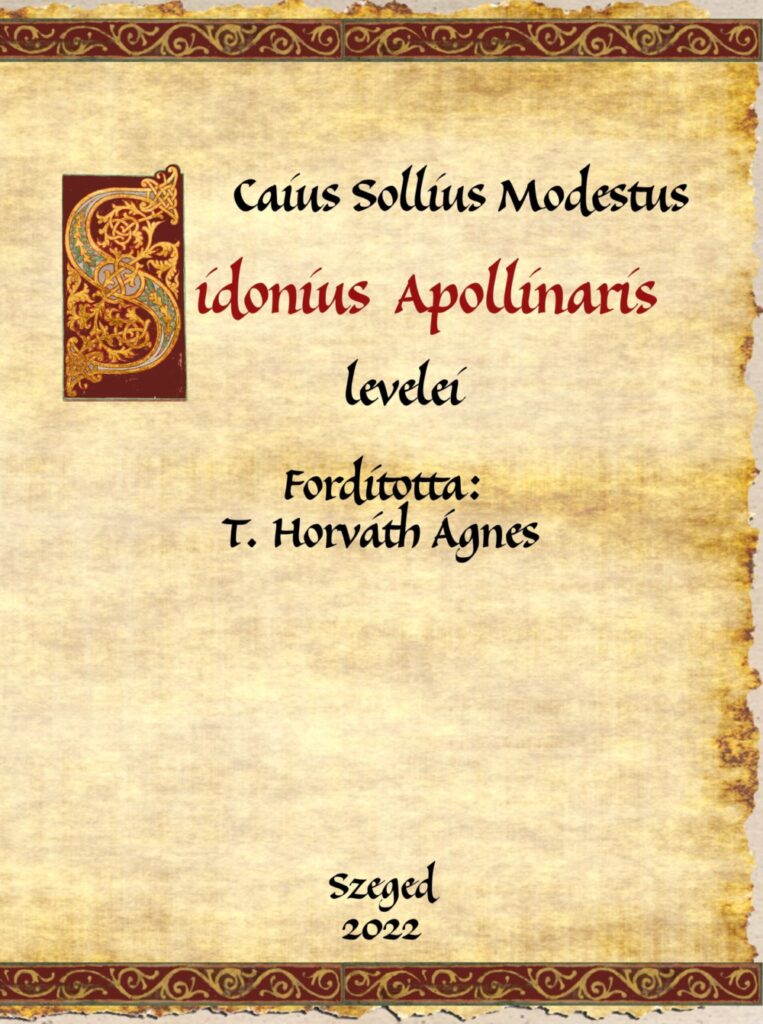

Ágnes T. Horváth has published her translation into Hungarian of the Letters: Caius Sollius Modestus Sidonius Apollinaris levelei, Szeged: JGYF Kiadó, 2022. Item in publisher’s catalogue here.

She provides the following explanation:

The volume consists of two parts. The first part contains the Hungarian translation of the letters and their explanation in footnotes. It is primarily a literary translation. The accompanying and detailed notes of commentary are not concerned with the Latin text, but rather with the content of the letters and the Hungarian wording. Mythological and other explanations in the commentary aim to help a general audience but also to facilitate further intertextual research. The translation and the notes are based on authoritative editions.

The second part of the volume contains some studies. The purpose of the author is to help Hungarian readers to get to know Sidonius better. The biographical section contains an overview of Sidonius’ life and a reconstruction of his family history. The biographical part includes secondary literature. The reconstruction of the history of his family starts with the analysis of his name and focuses on the investigation of the gens Sollia. It is based on published inscription material by means of which the author attempts to outline the rise of this gens (an article is forthcoming in English).

The final essay of the volume is the reception of Sidonius in Hungary. Sidonius was used as a generic example (speculum regis, personality sketch, panegyricus, propemptikon, epithalamium). Specific quotations of Sidonius can be traced back to the 15th century. Since the 19th century, his works have been used as historical sources, mainly due to his knowledge of the peoples of the Migration Period, especially the Huns and the city of Aquincum. Besides, the researchers of Hungarian prehistory (historians, archaeologists, phrenologists) also used his works. His descriptions and informations can be found in fiction as well, mainly in historical novels and in popular historical writings. The last subsection of the study is a brief summary of Hungarian research on Sidonius.

Appendices include a prosopography of Sidonius, the bibliography of the sources and secondary literature, and an index of names.