Roger Green’s TTH translation of Sidonius’ Poetry is now available in paperback.

Roger Green’s TTH translation of Sidonius’ Poetry is now available in paperback.

Another milestone in Sidonius scholarship has been reached: the first complete Italian translation of the Carmina minora by Stefania Santelia, with her text and explanatory notes. Silvia Condorelli wrote the introduction. Full title: Sidonio Apollinare. Carmina minora. Testo, traduzione e note a cura di Stefania Santelia. Saggio introduttivo di Silvia Condorelli, Studi latini n.s. 97, Naples: Paolo Loffredo, 2023.

Available here.

Gavin Kelly has put out the first ever edition of the paratexts of Sidonius’ panegyrics and carmina minora: ‘Titles and Paratexts in the Collection of Sidonius’ Poems’, in: Antonella Bruzzone, Alessandro Fo and Luigi Piacente (eds), Metamorfosi del Classico in età romanobarbarica, Nuova biblioteca di cultura romanobarbarica 2, Florence: Sismel–Galluzzo, 2021, 77-97.

Info volume here

Now announced by Liverpool University Press for publication on 1 November 2021:

Roger P.H. Green, Sidonius Apollinaris. Complete Poems, Translated Texts for Historians 76.

Sidonius Apollinaris was an inhabitant of southern Roman Gaul in the mid fifth century AD, when it was threatened by invasions from beyond the boundaries of the Roman Empire and by competing warlords. His many poetic works include three panegyrics to emperors at the beginnings of their reigns; these are carefully translated and annotated, and provided with comment and synopses. His multiple shorter poems, in a variety of metres, are translated into appropriate English and given separate introductions and notes of various kinds, historical and literary. There is an extensive and informative introduction to the whole work.

This book by Roger Green, a lifelong expert in Late Antiquity, gives a firsthand account of the political strife and manoeuvring of the times but also a vivid picture of the lives of his like-minded friends in an almost post-Roman episode of Rome’s existence. Sidonius was read widely in the Middle Ages, with a golden age in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and also in the fifteenth century revival of Late Antique literature. Today his poetry will awaken new study and interest, without the archaism of many older translations and with a fresh and updated approach to many issues.

Sigrid Mratschek is to write the first German translation of Sidonius’ Poems (provisional title: Sidonius Apollinaris, Panegyrici und carmina , lateinisch – deutsch, Sammlung Tusculum: de Gruyter) with an introduction, notes, a research essay and a selected bibliography.

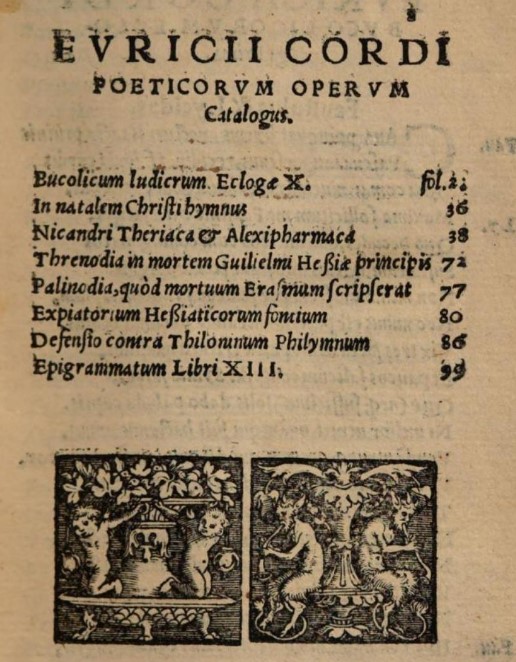

For his ‘Ad librum’, physician, botanist and poet Euricius Cordus (Heinrich Ritze, 1486 Hessen-1535 Bremen) was inspired by Sidonius’ famous envoi ‘Propempticon ad libellum’ (Carm. 24), up to its Phalaecian hendecasyllables, providing it with overtones of Catullus and Martial:

Ad librum

Non praeceps adeo ruas, libelle,

quin tuum prius audias parentem,

quae mandata tibi det exeunti.

Omnes quotquot ubique litteratos

cultoresque novem vides sororum,

meo nomine plurimum saluta.

Et si dignus eis videbor, ut me

antiquae numero sodalitatis,

extremum licet, adnotent, precare.

Dehinc ut rhinocerotas atque barros,

ronchos, auriculas ciconiasque

unius facias pili memento.

Demum quam potes eminus proculque

declines, fugias, abomineris

tectos tetrico hypocritas cucullo

rugosamque senum severitatem

et tantum placitos sibi sophastros,

invisum Latiis genus camenis.

Hoc est quod volui, osculare patrem

aeternumque vale, miselle fili.

See also the Receptions page Germany

Today, on the occasion of Sidonius’ death on a 21/23rd August some 1,540 years ago, a striking piece of literary reception giving an unexpected twist to the famous Carmen 12 on the impossibility of writing poetry among the barbarians.

Playwright and stage director Hartmut Lange (born 1937, in exile to West-Berlin from the DDR in 1965), in his 1972 play Staschek oder das Leben des Ovid on the dilemmas of compromising with the powers that be, has the protagonist meet Sidonius in Bordeaux instead of meeting Ovid in Tomi, as he expected. Staschek persuades Sidonius to smear his hair with rancid butter to assuage the barbarians. These, indeed, become nicer, but the stench makes Sidonius vomit all the time and prevents him from reciting his ‘ode to Venus’.

The play is a vivid satire of cowardice and self-interest in the face of totalitarianism (Horace and Vergil figure on the wrong side whereas Ovid refuses to collaborate). In the end, everybody has to compromise one way or another, even Sidonius.

See the Reception/Germany page for fuller detail on discussions by Kurt Smolak and Theodore Ziolkowski.

Text to be found in Hartmut Lange, Vom Werden der Vernunft und andere Stücke fürs Theater, Zürich: Diogenes. 1988, 307-41, esp. 338-39.

Tiziana Brolli continues the discussion of Carmen 13 on the lines of Stefania Santelia’s emendation of histriones to hic triones, and argues for different dates of the two sections of the poem in a new article ʻLa duplice prex del carme 13 di Sidonio Apollinare’, Wiener Studien 133 (2020) 215-35.

Online edition here

Claudia Schindler writes about the catalogue of poets in Carm. 9 as compared to similar catalogues in Ovid and Manilius: ‘Macht und Übermacht der Tradition. Dichterkataloge in der lateinischen Literatur von Ovid bis Sidonius’. More in Bibliography 2018.

Abstract

Catalogues introducing poets and their works are widespread in Roman literature. By mentioning a poetic predecessor the author of the catalogue places himself in the respective literary tradition. My contribution analyses three poetic catalogues from the Early Empire (Ov. Am. 1.15 and Manil. 2.1-52) and Late Antiquity (Sidon. Carm. 9) with a focus on the role of the self-referential author. The study shows that the (youthful) first person narrator of Ovid’s Amores is very confident in his own poetic ability and thus his position among his literary predecessors. The purpose of the catalogue is twofold: the author attempts to highlight his own poetic prowess and argues for poetic immortality in a long line of meticulous scientific arguments. Manilius, on the other hand, justifies his claim to be the first astronomical-astrological poet by highlighting the novelty of his own poetic concept in comparison to the literary tradition. He demonstrates that his originality derives not so much from his choice of material, but the method employed and his capable intellectual penetration of the subject matter. The late antique poet Sidonius Apollinaris designs his catalogue as recusatio, and explicitly distances himself from the literary tradition, which the first-person narrator perceives to be overwhelming and suppressive. The conflict between the self-fashioning and the highly learned poetry of Sidonius creates a paradox, which the recipient is challenged to identify. The three catalogues studied here represent a paradigm shift that transforms the literary tradition from an opportunity in Ovid and Manilius to an overpowering, incontestable concept in Sidonius, with which he nonetheless copes in his poetry.