Reception in France: Studies

Étienne Wolff, ‘Quelques jalons dans l’histoire de la réception de Sidoine Apollinaire’, in: Marco Formisano and Therese Fuhrer (eds), Décadence. ‘Decline and Fall’ or ‘Other Antiquity’?, Heidelberg: Winter, 2014, 249-62.

Remy de Gourmont (1858-1915), Le Latin mystique: les poètes de l’antiphonaire et la symbolique au moyen âge, preface by J.-K. Huysmans [replaced by Gourmont’s own in later editions; as to Sidonius, he did not want him to be dubbed a decadent], Paris: Mercure de France, 1892.

Pp. 57-60 (edition 1922) about Sidonius: ‘… Sidoine n’est pas un triste; il est gouailleur plutôt que mélancolique; il aime l’éclat des joies extérieures, même s’il doit souffrir de leur grossièreté …’

The blurb on the Les Belles Lettres website reads: ‘Non pas tant une anthologie qu’un sublimé de poésie spirituelle délicieusement décadente. Un “liseur” invétéré, un “créateur de valeurs” découvre dans les fleurs nouvelles germées de la décomposition de l’empire et simultanément de la langue et des normes classiques et arrosées par la foi chrétienne, des accents accordés aux aspirations de l’âme moderne malade d’infini et une écriture inédite, parente des recherches les plus exquises d’un Jules Laforgue ou d’un Albert Samain. Cet essai, qui fut une révélation pour Léon Bloy et Blaise Cendrars, reste encore aujourd’hui l’initiation la plus passionnante à la poésie religieuse de la latinité tardive et du Moyen Âge.’

Jean Anglade, Histoire de l’Auvergne, Paris: Hachette, 1974. Sidonius figures prominently in chapter 3, ‘L’Auvergne se latinise’.

Anonymous, ‘Sidoine Apollinaire: l’art du repli nostalgique en temps barbare’, academic course, c. 1990, YouTube

Sébastien Baudoin, ‘Présence-absence de Sidoine Apollinaire dans l’œuvre de Chateaubriand’, in: Rémy Poignault and Annick Stoehr-Monjou (eds), Présence de Sidoine Apollinaire, Clermont-Ferrand, 2014, 513-24.

‘Often quoted by Chateaubriand as an historian, Sidonius Apollinaris stands at the same time in and outside the text of ‘l’Enchanteur’. Taken as a reference legitimizing the comment, he also gives rise to a rewriting: the description of the Francs in Book 6 of Les Martyrs is thus, as Chataubriand himself admits, a free adaptation of Sidonius’ poetry in the Panegyric of Majorian. Between influence and inspiration, Sidonius Apollinaris figures as a revealing shadow which unveils complex processes of rewriting. It’s within this distance between unfaithful translation and rewriting that we analyze the creative poetic of our author.’

Marie-France de Palacio, ‘Mechanemata fin-de-siècle: Sidoine Apollinaire et la “décadence”’, in Rémy Poignault and Annick Stoehr-Monjou (eds), Présence de Sidoine Apollinaire, Clermont-Ferrand, 2014, 525-35.

‘After 1870, Sidonius Apollinaris makes a forcible entry into French literature. The fin de siècle fashions him into an intriguing paragon of decadence. A keen observer keeping aloof, acting as the last fence against the Barbarians, he conceals his uneasiness of mind under a dandiacal attitude. His poetry bears witness to some excessive stylistic elaboration, which made him worthy of serving as a pattern of Alexandrian affectedness, and led some critics to compare him to Stéphane Mallarmé or Jean Lombard.’

Reception in France: Forgery

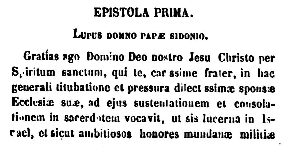

Lupus’ congratulation letter to Sidonius on his consecration as a bishop (Migne PL 58, cols 63-65) has been thought to be a forgery ever since Julien Havet (‘Questions mérovingiennes II, Les découvertes de Jérôme Vignier’, Bibliothèque de l’école des chartes 46 (1885) 205-71) adduced proofs for the inauthenticity of a group of fifth-century documents to which it belongs, which were published from the legacy of Father Jérôme Vignier (1606-1661), possibly inspired by (and rivalling with) recent publications by Duchesne and Sirmond, among others, and aimed to enhance papal authority and post-Tridentine orthodoxy. See, e.g., Ralph Mathisen, ‘PLRE II: Suggested Addenda and Corrigenda’, Historia 31 (1982) 377-78; Frank-Michael Kaufmann, Studien zu Sidonius Apollinaris, Frankfurt am Main 1995, 321-22; Jean-Louis Quantin, ‘Jérôme Vignier (1606-1661), critique et faussaire janséniste?’, Bibliothèque de l’école des chartes 156 (1998) 451-79. These letters were translated in 1706 by Canon Breyer of Troyes, probably unwittingly of their unauthenticity, and are the first translation of any part of Sidonius’ work. See the Translations page on this site, section French.

For the widespread practice in the Late Middle Ages and Early Modernity (1400-1700) of freely inventing the past in order to legitimize the present, see the KNAW research project The Quest for an Appropriate Past, organised by Karl Enenkel and Koen Ottenheym, and its future publication in Brill’s Intersections series. For a Dutch-language audience, they already published Oudheid als ambitie: De zoektocht naar een passend verleden 1400-1700, Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2017.

Reception in France: Fiction

Jean Anglade (1915-2017), Sidoine Apollinaire, with a preface by Rector Pierre Louis, Clermont-Ferrand: Volcans, 1963 (repr. in Auvergne encore, Paris: Omnibus, 2000).

Jean Anglade and Alain Vivier, L’Auvergnat et son histoire, 2 vols, ‘Des Crocodiles à Sidoine Apollinaire’ and ‘Du VIe siècle aux croisades’, Roanne: Horvath, 1979.

Elisabeth Szwarc (text), Jean-Michel Payet (illustrations), Sidoine Apollinaire. Un Gaulois contre les barbares, Paris: Épigones, 1993.

Guy Azaïs (1942-2021), Sidoine Apollinaire, mémoires imaginaires. Récit, Paris: Thélès, 2008. Second edition entitled Que le jour recommence. Mémoires, Paris: Société des écrivains, 2010.

Denis Montebello (1951-), Au dernier des Romains, Paris: Fayard, 1999.

Philippe Jamet (1961-), Le coucher du Tibre, Paris: Cylibris, 2000.

| Wikipedia

Christophe Grégoire, Avitus, l’empereur oublié, Clermont-Ferrand: De Borée, 2024.

Reception in France: Poetry

Daniel Aranjo, ‘Le latin de la vingt-cinquième heure (Sidoine Apollinaire 1930)’, in: Georges Cesbron and Laurence Richer (eds), La réception du latin du XIXe siècle à nos jours. Actes du colloque d‘Angers des 23 et 24 septembre 1994, Angers 1996, 365-84.

| text available on this site Contributions

Poems by Tristan Derème (1889-1941)

Daniel Aranjo, ‘Quatre poèmes modernes sur Sidoine Apollinaire, ses barbares, son époque (1931, 1994, 2004, 2005)’, 2014 (inedit.).

| text available on this site Contributions

Poems by Tristan Derème (1889-1941) and Georges Saint-Clair (pseud. of Jean Bégarie, 1921-2016)

For this and further poetry (Laurent Tailhade, Pierre Louÿs), see Filomena Giannotti, Scrinia Arverna. Studi su Sidonio Apollinare, Pisa 2021, 172-76.

Reception in France: Influence

Sidonius is among the poets quoted by Mico of Saint-Riquier (d. c. 853) in his Opus prosodiacum, a poetic florilegium to help learning words of difficult prosody. See David Butterfield, ‘Unidentified and misattributed verses in the Opus prosodiacum Miconis’, Museum Helveticum 66 (2009) 155-62.

| online

He is also present in Pierre d’Ailly (Petrus de Alliaco, 1351-1420), in the introductory lecture to his biblical course (Principium in Cursum Bibliae) at the University of Paris. Sidonius’ Letters are listed among the assets of the sermocinalium scientiarum, grammaticae videlicet et logicae, rhetoricae, et poeticae artis doctores, who have on offer a variety of authors:

‘Alii grammaticalia Prisciani rudimenta, alii logicalia Aristotelis argumenta, alii Rhetoricae Tullii blandimenta, alii poetica integumenta Virgilli; nec solum ista, quin immo Ovidii praesentant fabulas, Fulgentii mythologias, Odas Horatii, O <…> Orosii, Juvenalis Satyras, Senecae Tragoedias, Comoedias Terentiii, Invectivas Salustii, Sidonii Epistolas, Cassiodori Formulas, Declamationes Quintiliani, Decades Titi Livii, Valerii Epitomata, Martialis Epigrammata, Centones Homeri, Saturnalia Macrobii et generaliter singula quae vel suavis lyram Rhetoricae vel gravis Poeticae Musam resonant.’ (col. 612CD)

Further on, when attacking unreliable and selfish lawyers, d’Ailly freely cites Sidonius Ep. 5.7.2 in support:

‘Nam ut Sidonii verbis utar: “Hi sunt qui causas protendunt adhibiti, impediunt praetermissi, fastidiunt admoniti, obliviscuntur locupletati; hi sunt qui emunt lites, vendunt intercessiones, judicanda dictant, dictata convellunt, attrahunt litigaturos, protrahunt audiendos.”‘ (col. 614D)

| Text in Joannis Gersonii Opera Omnia, ed. Louis Ellies du Pin, Antwerp 1706, reprinted Hildesheim 1987, vol. 1, 610-17 | For explanation, see Louis Salembier, Petrus de Alliaco, Lille 1886, 197-99, in Gallica

I am grateful to Helga Köhler for pointing out this source.

In 1533, the copy of Pio’s Sidonius currently in the Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon (Rés Inc 158 (1)) figured in the library of the Lyonese lawyer Benoît Court as he was publishing a commented edition of Martial d’Auvergne’s Cinquante-et-un arrêts d’Amours. This is evidenced by underlined quotations in the text that return in the commentary.

| see Hélène Lannier, ‘Benoît Court en sa bibliothèque: Quelques indices du travail préparatoire à la rédaction des commentaires aux Arrêts d’Amours de Martial d’Auvergne’, Arts et Savoirs 10, ‘Bibliothèques des humanistes français’, 2018, online

André Thevet, Vrais Pourtraits et Vies des Hommes Illustres, Paris, 1584, vol. 3, book 6, chap. 85, pp. 486v-487v. Praises Sidonius for his subventions to impoverished intellectuals (’Sidoine amoureux des gens doctes’) and prefers to remain neutral in the stylistic debate on Cicero’s presumed normativity (’Langage de Sidoine, dequoy taxé’).

| read on Archive.org

Quotes in Michel de Montaigne‘s (1533-1592) Essais (4th edn 1588):

1.49 Des coutumes anciennes: ‘Les anciens Gaulois, dit Sidoine Apollinaire, portaient le poil long par le devant, et le derrière de la tête tondu, qui est cette façon qui vient à être renouvelée par l’usage efféminé et lâche de ce siècle’

3.5 Sur des vers de Virgile: tetrica sunt amoenanda iocularibus (Ep. 1.9.8)

3.9 De la vanité: laudandis pretiosior ruinis (Carm. 23.62).

The humanist legal expert Jacques Cujas (1522-1590) sought to better understand the Corpus iuris from late Latin poets, among them notably Sidonius. See Xavier Prévost, ‘Jacques Cujas et les poètes de l’Antiquité tardive’, CRMH 24 (2012) 379-403, online here.

Sidonius’ editor Jacques Sirmond (1559-1651), when still a young man, was summoned to Rome by the general of the Jesuit order to serve as his secretary. He describes his arduous voyage from Paris to Rome (August-December 1590) in a Hodoeporicum that is clearly reminiscent of Rutilius’ De reditu suo and, above all, Sidonius’ letter 1.5 with the description of his voyage from Lyon to Rome.

Download here (text and introduction in Luigi Monga, ‘L’Hodoeporicum de Jacques Sirmond, S.J.: Journal poétique d’un voyage de Paris à Rome en 1590′, Humanistica Lovaniensia 42 (1993) 301-22).

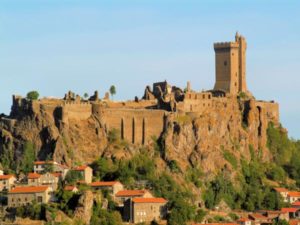

The Dukes of Polignac boasted a lineage which went all the way back to Sidonius. The first known history of the Polignac family is L’Histoire généalogique de la Maison de Polignac, by Gaspard Chabron (1570-after 1638), written towards 1625 (discussion and download here). It frames Sidonius’ grandfather as ‘le premier de la lignée de Messieurs de Polignac’ (p. 12), ‘le grand St Sidoine Apollinaire’ as the first to bear the title of count (p. 11), and the Castle of Polignac at Le Puy-en-Velay as their ancestral domain (p. 10). To support his claim, Chabron adduces Savaron’s authority in his comment on Ep. 4.6.2 solidae domus ad hoc aevi inconcussa securitas, ‘the security of the solid house, unshaken up to the present’ (which Sidonius is afraid might be disturbed by the enemy raids), Savaron says that this is the ancient home of the Apollinaris family in Velay, safely perched on the hill, and still visible in his day in all its age-old splendour. (Sirmond, however, saw the correct interpretation of domus: ‘family’.) Legend has it that there is a Temple of Apollo under its ruins.

Sons could be baptized ‘Sidoine-Apollinaire’ or ‘Apollinaire’, for instance Sidoine-Apollinaire-Gaspard-Scipion-Armand de Polignac (1660-1739), who made a military career, and Camille-Louis-Apollinaire de Polignac (1745-1821), bishop of Meaux. The family’s fairy-tale past made it to the gossip columns of the New York Times, 3 Dec. 1882.

See Christian Settipani, ‘Apollinaires et Polignac: état actuel d’une légende’, Héraldique et Genéalogie 106 (1988) 32-35, and ‘Les Polignac: quelques orientations pour la recherche historique et généalogique’, in Studies in Genealogy and Family History in Tribute to Charles Evans on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, London: Lindsay Brook, 1989, 327-53. For the castle, see Mélinda Bizri, ‘Polignac en Velay, relecture de l’origine et de l’évolution du site. Entre tradition, célébrité et réalité archéologique’, in: Anne-Marie Cocula and Michel Combet (eds), Château, naissance et métamorphoses, Bordeaux, 2011, 93-107 (download here).

Pierre Bayle (1647-1706), freethinking Huguenot, whose Dictionnaire historique et critique (1697, 2nd ed. 1702, 5th ed. 1740, English translation 2nd ed. 1734) was among the most popular works of the eighteenth century, repeatedly resorted to his Savaron copy of Sidonius to cite, and, if needs, criticize him. In volume 1 alone (A-Bi, in the English edition), Sidonius is referred to in the lemmata on Achilles, Anaxagoras, Apollonius, Apuleius, Arcesilas, Athenaeum, and Balbus. Sidonius is criticized for his sloppy treatment of philosophy concerning Anaxagoras and Arcesilas in Carm. 15.79-98, and Savaron for not noticing these errors. The figure of Apollonius of Tyana is attractive to Bayle for his unconventionality and being a challenge to authorities. Here Sidonius’ opinion of Apollonius comes in, with a quotation from Ep. 8.3. Bayle comments: ‘Sidonius Apollinaris has given us a description of Apollonius, which represents him as the greatest of heroes in philosophy. The author of this description does not forget to make his excuses to the Catholic church’ (p. 383). (Bayle thought that Sidonius had written Apollonius’ Life.)

In the years 1651-3, Guy Patin, dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Paris, sued one of its members, Jean Cartier, for the controversial use of antimony as a drug. In his memoir, he cites Sidonius among other authorities for the principle that only experts can assess each other: ‘Le saint évêque de Clermont, Sidonius Apollinaris, a dit en ses Épîtres: Qui non intelligunt artes, non mirantur artifices’ [Ep. 5.10.4].

Source: https://numerabilis.u-paris.fr/editions-critiques/patin/?let=8007. For the story of the row, see Elisabeth Labrousse and Alfred Soman, ‘La querelle de l’antimoine: Guy Patin sur la sellette’, Histoire, économie et société 5 (1986) 31-45.

Jean-Baptiste Du Bos (1670-1742), Histoire critique de l’établissement de la monarchie française dans les Gaules, vol. 1 (1734, 2 1742), is a sustained reading, cum extensive translations, of Sidonius’ Panegyrics and Letters, guided by Duchesne and Sirmond.

For an assessment of the abbé Du Bos and his Histoire critique, see Ian Wood, The Modern Origins of the Early Middle Ages, Oxford, 2013, 29-36.

Another sign of the importance Du Bos attached to Sidonius is the link he sees between Sidonius’ picture of a gallery of philosopher portraits and Raphael’s School of Athens. The passage in question is from the Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et sur la peinture, published in Paris in 1709, and repeatedly reprinted and enlarged (transl. Thomas Nugent, 1748):

We find by the epistles of Sidonius Apollinaris [the passage from Ep. 9.9 is quoted in a footnote], that the illustrious philosophers of antiquity had each of them their particular air, figure, and gesture, which were peculiarly appropriated to them in painting. Raphael has made a good use of this piece of erudition from Apollinaris, in his picture of the school of Athens.

This observation is adopted in Diderot & d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, vol. 17 (1765) 484. It belongs in the tradition of the classisizing, philosophical interpretation of the School of Athens which originated in Paris and Rome during the seventeenth century (Fréart and Bellori) as against Vasari’s theological reading. For this debate, see Bram Kempers, ‘Words, Images and All the Pope’s Men. Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura and the Synthesis of Divine Wisdom’, in: I. Hampsher-Monk et al. (eds), History of Concepts. Comparative Perspectives, Amsterdam, 1998, 131-65. (See the Reception Germany page, for a similar observation by Herman Grimm.)

Alexandre Dumas père (1802-1870), Impressions de voyage. Le Midi de la France, vol. 2, Bruxelles: Hauman, 1841, p. 132. Dumas writes in his chapter on Arles:

La puissance romaine s’éteignit à Arles avec Jules Valère Majorien. Il traversa les Alpes en 438, s’empara de Lyon, et, trouvant, comme Constantin, Arles merveilleusement située, il résolut d’y établir sa cour impériale. Ce fut pendant son séjour en cette ville et dans le palais de Constantin, qu’il invita Sidoine Apollinaire à s’asseoir à sa table ; et c’est à cette circonstance que nous devons la lettre du poëte à Montius son ami, lettre dans laquelle il consigne les détails de ce grand festin, où sept grands seigneurs avaient assisté, et où il fait la description du palais, orné, dit-il, de magnifiques statues placées entre des colonnes de marbre.

| read, with references

Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), À rebours, Paris: Charpentier, 1884. Jean Des Esseintes admires Sidonius’ luscious style. See David Amherdt, ‘Sidonius in Francophone Countries’, in: J.A. van Waarden and G. Kelly (eds), New Approaches to Sidonius Apollinaris, Leuven (2013) 23. See also R. Chevallier, ‘La bibliothèque de Des Esseintes ou le latin “décadent”: une question toujours d’actualité’, Latomus 61 (2002) 163-77.

See above at Remy de Gourmont.

Roland Barthes, The Preparation of the Novel: Lecture Courses and Seminars at the Collège de France, 1978-1979 and 1979-1980 (transl. Kate Briggs), New York: Columbia UP, 2011; see p. 8:

Barthes was so delighted to have found an exception among languages in Sidonius’ unique verb scripturire (Ep. 7.18.1) that he always applied it as the word par excellence for the attitude of ‘wanting-to-write’ (’vouloir-écrire’).

Laurent Nunez, Il nous faudrait des mots nouveaux, Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 2018, pp. 169-82 chapter ‘Taciturire’.

‘Taciturio: … Je n’ai plus très envie de m’exprimer sur tout ce qui arrive.’ Among other foreign words, Nunez is struck by taciturire and scripturire, cites Deleuze’s ‘Écrire, c’est propre. Parler, c’est sale’, and, after a reading of Carm. 12, concludes that, by introducing barbarisms into the language, Sidonius became a sort of barbarian poet himself. – Look up in catalogue

Reception in France: Various

- The tourist office of Clermont-Ferrand ends its booklet ‘Ville avec vues’ with Sidonius’ words ‘Une fois que les étrangers ont connu l’Auvergne, ils y perdent le souvenir de leur patrie’. A modest tribute among the much more prominent citizens Vercingetorix, Urban II, and Pascal, who are even represented in the pavements.

- The name ‘Sidoine Apollinaire’ is remembered in the Lycée Sidoine Apollinaire at Clermont-Ferrand and in street names in this and various other towns in Southern France, among them Lyon. Puget-Ville (dept. Var, map) boasts a Saint Sidoine bell tower which once dominated the homonymous 11th-century parish church. It gives its name to one of the local vineyards.

- Among Clermont’s saints, Sidonius is still venerated as evidenced, for instance, by the liturgy of a priestly ordination in the cathedral of Clermont-Ferrand in December 2020. On the first day of preparation Saint Austremonius is invoked, on the second Sidonius. One prayer goes:

- The Priestly Society of Saint Pius X, on 19 January 2021, commemorates ‘the 1,550th anniversary of the accession of St. Sidonius Apollinaris to the episcopal see of Clermont-Ferrand’.

Seigneur tout puissant et éternel, tu as choisi l’évêque saint Sidoine pour en faire le pasteur de ton Eglise de Clermont en des temps difficiles. A son exemple, apprends-nous à garder confiance dans l’adversité et à rester fermes dans la foi.

Source: Service diocésain de vocations de Clermont, 4-12 December 2020

- The church of Aydat (ancient Avitacum) is dedicated to Saint Sidoine Apollinaire. It was visited on 8 July 1783 by the Abbot Cortigier, canon of the cathedral of Clermont, and company in search of Sidonius’ villa. They admired the ‘Hic sunt duo innocentes et S. Sidonius’ monument and heard about the lasting veneration for Sidonius invocated against fever:

Source: Bulletin historique et scientifique de l’Auvergne 7 (1887) 125-29, on page 128

| see on this site: the Gallery page and Bibliography 1887

- The ‘prix Sidoine-Apollinaire’ was a prize for a literary oeuvre, either documentary or fictional, that contributed to the knowledge of the Auvergne or of Rhône-Alpes. It was awarded in 1959 and in the 1970s and 80s.

Source: Wikipedia Prix Sidoine-Apollinaire