Reception in Italy: Modern and Contemporary

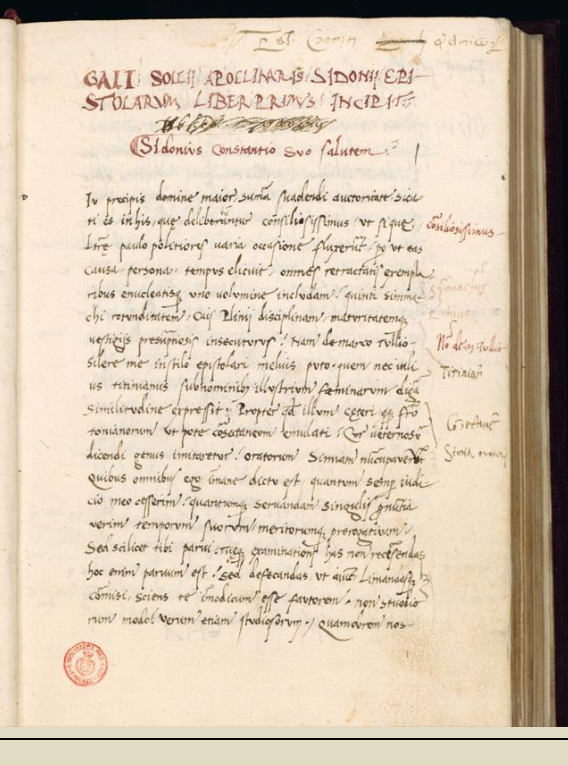

Giacomo Leopardi‘s (1798-1837) readings in his youth in the family library at Recanati left traces in his early work, studied by Giulia Marolla, ‘Leopardi lettore di Sidonio Apollinare e Mamerto Claudiano’, Bollettino di Studi Latini 52 (2022) 592-600.

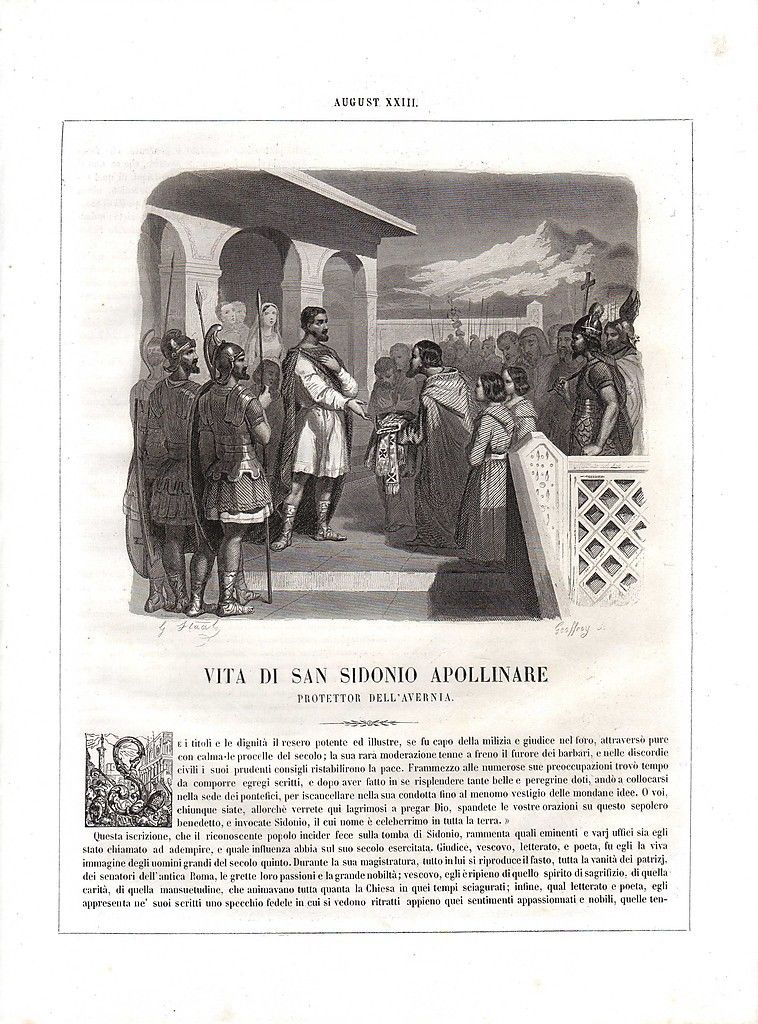

Sidonius’ life, subtitled ‘Protettor dell’Avernia’, figures, lavishly illustrated with steel engravings, in Vite de’ Santi scritte di nuovo da letterati francesi e italiani. Edizione illustrata da magnifiche incisioni in legno e in acciajo, published by Tipografia E. Alberghetti e C., Prato, 1850.

Vico Faggi (pseudonym of Alessandro Orengo, 1922-2010) wrote this dedicatory poem in his volume of translations, Sidonio Apollinare: Carmina, Genua: S. Marco dei Giustiniani, 1982:

Al poeta Sidonio Apollinare

Il tuo sapere, i tuoi versi, che potevano,

Sidonio Apollinare, dinanzi

la fatale caduta? Poi che il tempo

della fine era giunto. Anche gli dèi

pallidi fuggivano. Ma il tuo braccio

si levò a difesa di un mondo

che amavi. Era giusto, inutile. Rimane

il ricordo di un gesto, i tuoi versi.

Published in a limited edition, copies are enriched with separate etchings by Valeriano Trubbiani.

Umberto Eco, Vertigine della lista, Milan: Bompiano, 2009.

In chapter 6, ‘Liste di luoghi’, the Laus Narbonis in Sidonius’ Carmen 23, 37-68 figures among the examples.

Giulio Castelli, Il romanzo dell’Impero Romano, Roma: Newton Compton, 2013.

‘C’è stato un tempo in cui i vessilli di Roma annunciavano al mondo un dominio immortale. Ora quel tempo è finito e i confini della città sono stati oltraggiati da torme di barbari. In un impero ormai disgregato e corrotto, tra intrighi di palazzo, complotti, assedi e passioni, rivivono personaggi pronti a sacrificare la loro intera esistenza per il riscatto di Roma. Sullo sfondo, il torbido affresco del V secolo e le decadenti province romane. Fondendo letteratura e rigore storico, Castelli ci accompagna in un viaggio senza tempo, da Roma a Costantinopoli, dall’Illiria alla Gallia, fino alla remota Britannia, per farci assistere ad un’ultima epica battaglia…’

See the publisher’s catalogue

In a chapter on modern reception of Sidonius in the Edinburgh Companion to Sidonius Apollinaris, Filomena Giannotti (Siena) discusses this trilogy and Sidonius’ role in it.

Alberto Giorgio Cassani, ‘Ravenna fantastica: da Sidonio Apollinare a Michelangelo Antonioni’, in: Marisa Zattini (ed.), Onorio Bravi, Ravenna fantastica! con poesie di Nevio Spadoni, Cesena: Il Vicolo, 2015, 13-19 (exposition catalogue 10 October-7 November 2015, Ravenna).

Claudio Pasi, Ad ogni umano sguardo, Turin: Aragno, 2019, p. 21 (with note on p. 139) features a poem titled ‘Una lettera del 467′, combining Sidonius’ epistles 1.5 and 1.8 for the latter’s voyage from Lyon to Rome via Ravenna. It is in the form of a letter by Candidianus (the addressee of 1.8) and begins as follows:

Candidiano saluta Sidonio.

Per arrivare, amico, nel mio esilio

né felice né triste, dovrai scendere

per fiumi che costeggiano foreste

di aceri e di querce, …

For a presentation, see A. Fo, ‘Schegge odeporiche dell’odierna recezione di poeti latini: fra Catullo, Ovidio e Rutilio Namaziano’, Semicerchio 63 (2020) 37-44, esp. 39-40, and Filomena Giannotti, Scrinia Arverna: Studi su Sidonio Apollinare, Pisa: ETS, 2021, 178-80.