Reception Other

Canada

Jean Marcel (pseud. of Jean-Marcel Paquette), Triptyque des temps perdus, vol. 3 Sidoine ou la dernière fête, Montreal: Leméac, 1993.

‘Between 1989 and 1993, Jean Marcel published Triptyque des temps perdus, a trilogy of three novels shot through with generic and chronological tensions. Having defined the Triptyque as belonging to the genre of the historical biographical novel, we offer a two-part analysis of the paradoxical relationship between writing of a dim and remote past—the decline of the Roman empire—and the undeniable modernity of Jean Marcel’s work. On the one hand, through the antique figures of Hypatia, Jerome and Sidonius, Marcel speaks of the modern era and its constituent tension between what is perishable and what is changeless. On the other hand, he starts from questions raised by modernity to renew some of the formal aspects — documentation, utterance, narration — of a genre seen as obsolete: the biographical historical novel. In terms of writing, Triptyque ultimately shares the modern literary concerns of other contemporary fictions with a biographical dimension.’

See source, Robert Dion et al., ‘Le Triptyque des temps perdus de jean Marcel, Mordernité du roman biographique historique’, Voix et image 30 (2005) 35-50. See further Filomena Giannotti, Nei pensieri degli uomini: momenti della fortuna di Ambrogio, Girolamo e Agostino, Bologna: Pàtron, 2009, esp. 127-31 and 142. By the same author, in Edinburgh Companion to Sidonius Apollinaris, Edinburgh 2020, 712-17, and in Scrinia Arverna. Studi su Sidonio Apollinare, Pisa 2021, 133-42.

Czechia

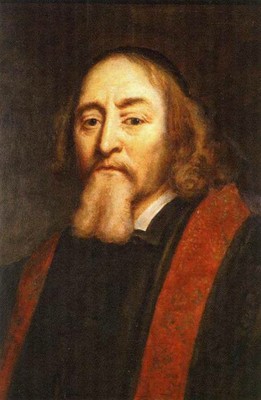

One of many lists in Jan Amos Comenius’ The Labyrinth of the World (1631), this one in particular, of philosophers in chapter 11, reminds of Sidon. Ep. 4.3.5-7 and Alanus Anticlaudianus 2.343-62 – all of them drawn up according to the determinatio figure:

There I beheld Bion sitting down quietly; there Anacharsis walked to and fro, Thales flew, Hesiod ploughed, Plato hunted in the skies for ideas, Homer sang, Aristotle disputed, Pythagoras was silent, Epimenides slept, Archimedes moved the earth, Solon wrote laws and Galen prescriptions, Euclid measured the hall, Kleobulus inquired into the future, Periander measured out their duties to men, Pittacus warred, Bias begged, Epictetus served, Seneca praised poverty while surrounded by tons of gold, Socrates informed everyone that he knew nothing; Xenophon, on the contrary, promised to teach everyone everything; Diogenes, peeping out of a tub, insulted all who passed by; Timon cursed all, Democritus laughed at all this; Heraclitus, on the other hand, cried; Zeno fasted, Epicure feasted; Anaxarchus said that all things were nothing in reality, but only appeared to exist (transl. Count Lützow, New York, 1901; see also the translation by Howard Louthan and Andrea Sterk, New York, 1998).

The function of ‘chains of words’ in the Labyrinth is discussed in Renate Lachmann, ‘Rhetorische Instrumentierung in Comenius’ Seelenbildungsroman Labyrinth der Welt und Paradies des Herzens’, in: Holt Meyer and Dirk Uffelmann (eds), Religion und Rhetorik, Stuttgart, 2007, 48-64.

For variations on this list of the Seven Sages and of classic philosophers, see Auson. Ludus VII Sap.; Aug. Civ. 8.2; Claud. Paneg. Theod. [17].70-83; Sidon. Carm. 2.156-81, 15.51-125, 23.111-19.

Hungary

John Vitéz of Zredna (c. 1408-1472), one of the most prominent scholars, patrons of arts, politicians and diplomats of the 15th-century Kingdom of Hungary, the first Hungarian chancellor with Humanist interests and archbishop of Esztergom; at a time when Ciceronian Latinity was not an inevitable standard, especially among Central European early Humanists, he had as his stylistic ideals Symmachus and Sidonius Apollinaris, rather than Cicero and Pliny (according to Matthias Bél in the 18th-century first edition of Vitéz’s letters).

See Farkas G. Kiss, ‘Origin Narratives’, The Hungarian Historical Review 8 (2019) 471-96, esp. 483 n. 55.

For an edition of Vitéz’ works, see Iván Boronkai (ed.), Iohannes Vitéz de Zredna. Opera quae supersunt, Bibliotheca scriptorum medii recentisque aevorum, S.N. 3, Budapest: University Press, 1980.

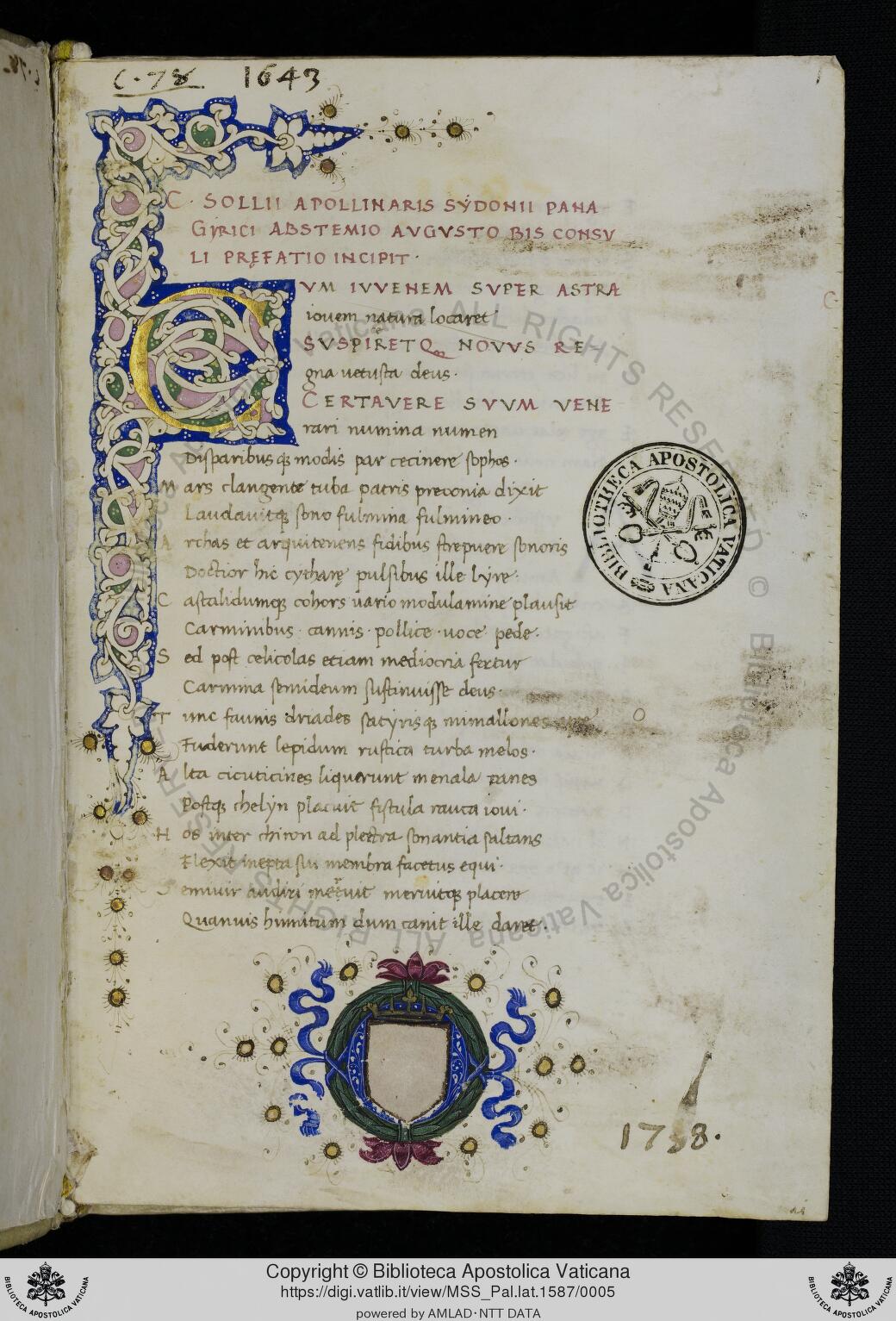

Vitéz probably owned MS Pal. Lat. 1587, dated 1468, now in the Vatican, which contains marginalia in his handwriting and, after his death, entered the collection of king Matthias Corvinus. It is a composite manuscript which, on ff. 1r-73v, features Carm. 1-15, 17-22, 16, 24, 22, 23.

See Klára Csapodi-Gárdonyi, Les manuscrits copiés par Petrus Cenninius. Liste revue et augmentée, Miscellanea codicologica F. Masai dicata, Ghent, 1979, 413-16.

Despite the above, Sidonius as such is not mentioned in Hungarian scholarship prior to the 18th century (MS pointed out and communication by Ágnes Tóth-Horváth).

Co-founder with Theodor Herzl of the World Zionist Organization, Max Nordau, born in Budapest, denounced the moral and cultural degeneration of the fin-de-siècle in Entartung, Berlin, 1893:

‘The truth is that these degenerate writers [like Gautier, Baudelaire, and Huysmans] have arbitrarily attributed their own state of mind to the authors of the Roman and Byzantine decadence, to a Petronius, but especially to a Commodianus of Gaza, an Ausonius, a Prudentius, a Sidonius Apollinaris, etc., and have created in their own image, or according to their morbid instincts, an “ideal man of the Roman decadence.”’ (Degeneration, trans. George L. Mosse, London, 1993, 301)

Lithuania

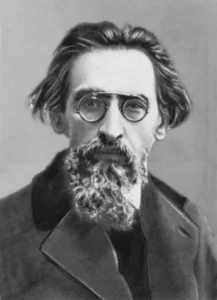

The Lithuanian/Russian philosopher and cultural historian Levas Karsavinas (Лев Платонович Карсавин, 1882-1952) got his doctorate with a thesis entitled : Из истории духовной культуры падающей римской империи. Политические взгляды Сидония Аполлинария, ‘From the History of the Spiritual Culture of the Falling Roman Empire. The Political Views of Sidonius Apollinaris’ (St Petersburg 1908).

See source | link to the text via Wikipedia/Lev Karsavin/Works

Portugal

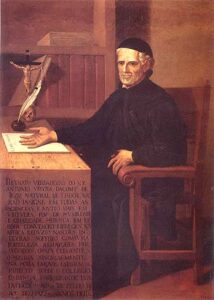

In 1655, the Jesuit court preacher Padre Antônio Vieira held his famous Sermon of the Good Thief (Sermão do Bom Ladrão) in Lisbon in the presence of King João IV, his court, judges, ministers, and counsellors, denouncing the greed and corruption in the colony of Brasil that were rife in the Portuguese leading class, including enslavement of the natives. He cites Sidonius’ Seronatus among other arguments in this passage:

Diógenes que tudo via com mais aguda vista que os outros homens viu que uma grande tropa de varas e ministros da justiça levava a enforcar uns ladrões e começou a bradar: lá vão os ladrões grandes a enforcar os pequenos … De Seronato disse com discreta contraposição Sidônio Apolinário: Non cessat simul furta, vel punire, vel facere. Seronato está sempre ocupado em duas coisas: em castigar furtos, e em os fazer. Isto não era zelo de justiça, senão inveja. Queria tirar os ladrões do mundo para roubar ele só! Declarando assim por palavras não minhas, senão de muito bons autores, quão honrados e autorizados sejam os ladrões de que falo, estes são os que disse, e digo levam consigo os reis ao inferno.

Diogenes, who saw everything more keenly than other men, saw that a large troop of courtiers and ministers of justice led some thieves away to hang them, and began to shout: There go the big thieves to hang the little ones … Sidonius Apollinaris said pointedly of Seronatus: Non cessat simul furta, vel punire, vel facere [Sidon. Ep. 2.1.2]. Seronatus is always busy with two things: punishing thefts, and doing them. This was not zeal for justice, but envy. He wanted to take the thieves out of the world to steal it alone! This makes plain, in words not of mine but of very good authors, how honoured and authorized are the thieves of whom I speak. These are the ones I meant, and I say: take the kings to hell with them.

Source PasseiWeb

Spain

A short hagiography by Pedro de Ribadeneyra (1526-1611) in Flos Sanctorum (1599-1601), at 23 August, pp. 472-75 of the Madrid 1716 edition.

In 1882, in the first volume of his Cantos populares españoles, Francisco Rodriguez Marin concludes his introduction with this apology to his readers, citing Sidonius Apollinaris: ‘Illud vere nec verecunde peto, ut praesentibus ludicris ignoscatis libenter’ (p. 39; free after Ep. 9.13.6).

A sonnet by Jesús Pardo (b. 1927), in his volume of poetry Gradus ad mortem IV-V-VI, Madrid, 2008, p. 55, with Carm. 7.55-56 for its motto:

Sidonio Apolinar, me traes albricia:

si tu Europa, Sidonio, se despieza,

la mía, en torno a mí, se despereza:

Roma en ti acaba, en mí se reinicia.

En tu Roma mi Europa se refina

trocando en gozo tu tristeza suave.

Doctor en decadencia, tu alma ingrave

augura lo que el tiempo nos destina.

Europa unida, en Roma disgregada

renace intacta contra el tiempo inerte

en cuya fauce acabará su gloria.

El tiempo, siempre el tiempo. Todo y nada

es el tiempo: se vierte y se desvierte:

aviso tú, Sidonio, a nuestra euforia.

© Jesús Pardo de Santayana

United States of America

Fiction

Steve White (1948-), Legacy, The Disinherited Series 2, Wake Forest, NC: Baen Books, 1995.

‘”It is, of course, premature to congratulate you, my dear Sidonius. We must observe the proprieties and wait until your election has become official.” Bishop Faustus of Riez chuckled patronizingly.’

‘These novels use Geoffrey Ashe’s theory (The Discovery of King Arthur, Garden City, N.Y.: AnchorPress/Doubleday, 1985) that the British chieftain and Sidonius’ correspondent Riothamus was the historical basis for the legend of King Arthur.’

‘Legacy involves time travel rather than alternate history, as does Debt of Ages, and the characters witness Riothamus’ actual campaign in Gaul. Sidonius is the viewpoint character in the Prologue. Then he reappears about halfway through; the first half is the space-adventure part, before the characters get hijacked into time travel.’ (Communications by the author).

Steve White, Debt of Ages. The Disinherited Series 3, Wake Forest, NC: Baen Books, 1995.

King Arthur saved the galaxy. Now, who will save the once and future king? ‘The Restorer was dying. I knew him for the Restorer at the moment I first met him, thought Sidonius Apollinaris, known to the world these past eight years as His Holiness Gaius II, keeper of the keys of Saint Peter.’ Hard-core SF with real-world biographical inlays concerning Sidonius Apollinaris, Ecdicius, the patriarch Acacius and pope Gelasius. In an alternate timeline, Sidonius overcomes the Visigoths and is appointed bishop of Rome.

Music

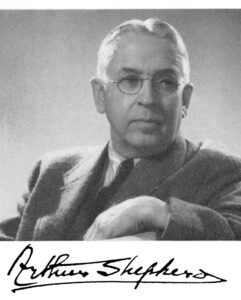

Arthur Sheperd (1880-1958), Invitation to the Dance for chorus and orchestra (1936) on a poem by Howard Mumford Jones (1892-1980) after Sidonius Apollinaris, Carm. 37 in Ep. 9.13.5 ‘Age, convocata pubes’:

Spread the board with linen snow.

Bid ivy and the laurel grow

Over it, and with them twine

The green branches of the vine.

Bring great baskets that shall hold

Cytisus and the marigold,

Cassia and starwort bring

And crocuses, till everything,

Couch and sideboard, all shall be

A garland of perfumery.

Then with balsam-perfumed hand

Smooth disheveled locks; and stand

Frankincense about, to rise —

An Arabian sacrifice —

Smoking to the lofty roof.

Next, let darkness be a proof

That our lamps with day may vie,

Glittering from the chamber’s sky.

Only in their bowls be spilled

Oil nor grease, but have them filled

With such odorous balm as came

From the east to give them flame.

Then bid loaded servants bring

Viands that shall please a king,

Bowing underneath the weight

Of chased silver rich and great.

Last, in bowl and patera

And in caudron mingle a

Portion of Falernian wine

With due nard, while roses shine

Wreathed about the cup and round

The cup’s tripod. We’ll confound —

Where the garlands sway in grace

From vase to alabaster vase —

All the measures of the dance;

And our languid limbs shall glance

In a mazy Mænad play.—

Step and voice shall Bacchus sway,

And in garment let each man

Be a Dionysian!

See William S. Newman, ‘Arthur Sheperd’, The Musical Quarterly 36,2 (1950) 159-79, esp. 172; Archives West, entry ‘Arthur Sheperd’, Choral works 9.1; WorldCat, entry ‘Invitation to the dance’. Text from Philip S. Allen, The Romanesque Lyric, with renderings into English verse by Howard M. Jones, University of North Carolina Press, 1928, reprinted in An Anthology of World Poetry, ed. Mark Van Doren, New York, 1928, p. 453-54, where Sheperd may well have found it; also available here and here.

Various

Edward Hirsch, A Poet’s Glossary, Boston, 2014, 438, uses Sidonius’ term versus recurrentes and his example Roma tibi subito motibus ibit amor (Ep. 9.14.4) to illustrate the notion of a palindrome.

General / Works of Reference

Gilbert Highet, The Classical Tradition

Gilbert Highet (1906-1978), The Classical Tradition. Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature, Oxford, 1949.

Page 189: Sidonius in Villey’s list of Montaigne’s reading [see Essais 1.49, 3.5, and 3.9; see also France > Michel de Montaigne on this website].

Page 220: ‘Nearly all Greek and Roman lyric poetry was destroyed or allowed to disappear during the Dark Ages. … In Latin we have … the work of a few third-raters like Sidonius Apollinaris …’

Pages 471-72: A pessimistic comparison, as to the free exchange of knowledge, between scholarship in Europe and America after World War II and Sidonius’ times: ‘Are these shadows on so many of our horizons the outriders of another long night, like that which was closing in upon Sidonius?’ The equation is inspired by the Oxford archaeologist and army officer Stanley Casson (1889-1944).

The Classical Tradition

Anthony Grafton et al. (eds), The Classical Tradition, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Harvard, 2010, registers some classical influences on Sidonius, but contains no material on Sidonius’ reception in later times.

Classical Reception in English Literature and Translation

The first volume of The Oxford History of Classical Reception in English Literature (OHCREL), which covers the period 800-1558, contains the following entries mentioning Sidonius:

Rita Copeland, ‘The Curricular Classics in the Middle Ages’, pp. 21-34

26 Alexander Neckham (1157-1217), born and grew up in England, and lived part of his life in St Albans. Also a schoolmaster at Dunstable, and then studied and taught in Paris. Around the turn of the century he joined the Augustinian canons at Cirencester, where he taught for some years before becoming abbot in 1213. In a work designed for the schoolroom, the Sacerdos ad altare (written while he was at Cirencester), Neckham lays out a course of study across the liberal arts and the specialized fields of medicine, law, and theology. As part of the early grammatical curriculum, by way of an entry into literary culture, he provides a list of authors whose works must be known. These include Sidonius.

James Willoughby, ‘The Transmission and Circulation of Classical Literature: Libraries and Florilegia’, pp. 95-120

105 ‘A compiler, Peter of Cornwall (1140-1220), Augustinian prior of Holy Trinity, Aldgate, in London, quoted Virgil in his vast Book of Revelations. ‘O terque quaterque beatum’ goes back to Aeneid 1.94, but the context suggests rather that Sidonius Apollinaris … was Peter’s filter, for Sidonius had used the same quotation in a letter to Gaudentius, tribune and notary at the court in Gaul …. Such quotations and their embedded context are a reflex of the writer’s art, but they are a reflex too of reading and understanding the work of classical authorities as collections of exempla, of which the compilation of (p. 106) phrases from common authorities into textbooks was a natural consequence.’

106 An English copy of the Florilegium Angelicum, late 14th century, Oxford, Trinity College, MS 18, contains extracts from Sidonius.

James P. Carley and Ágnes Juhász-Ormsby, ‘Survey of Henrician Humanism’, pp. 515-40

524 Juan Luis Vives provided a full educational programme for Princess Mary (daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon) in his De institutione foeminae Christianae. ‘Vives’ approach to the teaching of grammar and his rigorous list of approved authors echo Colet’s earlier provisions for St Paul’s, particularly his concern to show the sound moral content of pagan writings. Accordingly, Mary was advised to draw lessons from authors frequently used in grammar schools: Cicero, Seneca, Justin, Florus, Valerius Maximus, and from Latin translations of Plutarch and Plato. Unlike the schoolboys, however, she was advised to avoid Virgil, Ovid, Horace, Terence, and Plautus because of their ambiguous morality. Vives recommended instead the writings of Augustine, Erasmus, More, and the Christian poets Prudentius, Sidonius, Paulinus, Arator, Prosper, and Juvencus.’

No mention of Sidonius Apollinaris is made in the second to fourth volumes, covering 1558-1660, 1660-1790, and 1790-1880 respectively (apart from Sidonius as a reader of Statius, along with Ausonius and Claudian, in vol. 3, p. 78). In volume 4, Jennifer Wallace (‘“Greek under the trees”: Classical Reception and Gender’, 243-78, esp. 250-51) discusses Charlotte Mary Yonge’s attitude towards classical education for girls (The Daisy Chain, The Book of Golden Deeds).

Publication of the series began in 2012 ; it is to comprise five volumes.

There is no mention either in Stuart Gillespie, English Translation and Classical Reception. Towards a New Literary History, Chichester 2011. The same is the case with Peter France et al., The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English, vol. 1 up to 1500, vol. 2 1550-1660, vol. 3 1660-1790, vol. 4 1790-1900, (vol. 5 up to 2000), Oxford 2005-…

Classical Reception in Dutch and Flemish Literature

Patrick De Rynck and Andries Welkenhuysen, De Oudheid in het Nederlands, Baarn (1992) 342-43, has the following entry on Sidonius Apollinaris:

(Gaius Sollius Modestus (?) Apollinaris Sidonius; ca. 430-ca. 485 n.C.). Latijns-christelijk schrijver en dichter, geboortig van Lyon. In zijn 24 Carmina (Gedichten) prijst en vleit hij de groten van zijn tijd, o.m. zijn schoonvader keizer Avitus. Na zijn aanstelling tot bisschop van Clermont-Ferrand (469) schreef hij nog hoofdzakelijk brieven, achteraf gebundeld in 9 boeken. In deze 147 retorisch verzorgde maar inhoudarme Epistulae zijn vaak gedichten en metrische inscripties verwerkt.

*Brakman, Opstellen, 1919, p. 147-176. – Met (proza)vert. van fragm. uit Carm. en Epist.

*Duinkerken, Wereldhistorie, 1946, p. 25-26. – Vert. van Epist. 4, 20 (over een prinselijke bruiloft).

*Hadas/Schwartz, Geschiedenis van Rome, 1959, p. 259-261. – Fragm. uit Epist. 1, 2 (over koning Theoderik II).

*De tijd van Rome’s laatste keizers; veertien brieven van Apollinaris Sidonius… vertaald en ingeleid door Engelbert H. ter Kuile, Zutphen, Walburg Pers, 1976.

Brill’s New Pauly

Sidonius in Brill’s New Pauly 13-15/3, Manfred Landfester (ed.), Rezeptions- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte:

Mittellatein 15/1, 455 (Stilanalyse hoch-MA Musterautoren: Galfredus von Vinsauf ‘modus et mos Sidonianus’);

Niederlande und Belgien 15/1, 985;

Rhetorik 15/2, 776-7 (hoch-ma. poetria: descriptio a capite ad pedes, determinatio und conversio);

Rom 15/2, 874, 901;

Zeitrechnung 15/3, 1190.

No mention of Sidonius is made in Brill’s New Pauly Supplements 1, vol. 5: Christine Walde and Brigitte Egger (eds), The Reception of Classical Literature, Leiden 2012